GRAND RAPIDS, Minn. – John Kelsch gestures to a waist-high black-topped pedestal.

It’s empty and that’s the point. It was a crime scene.

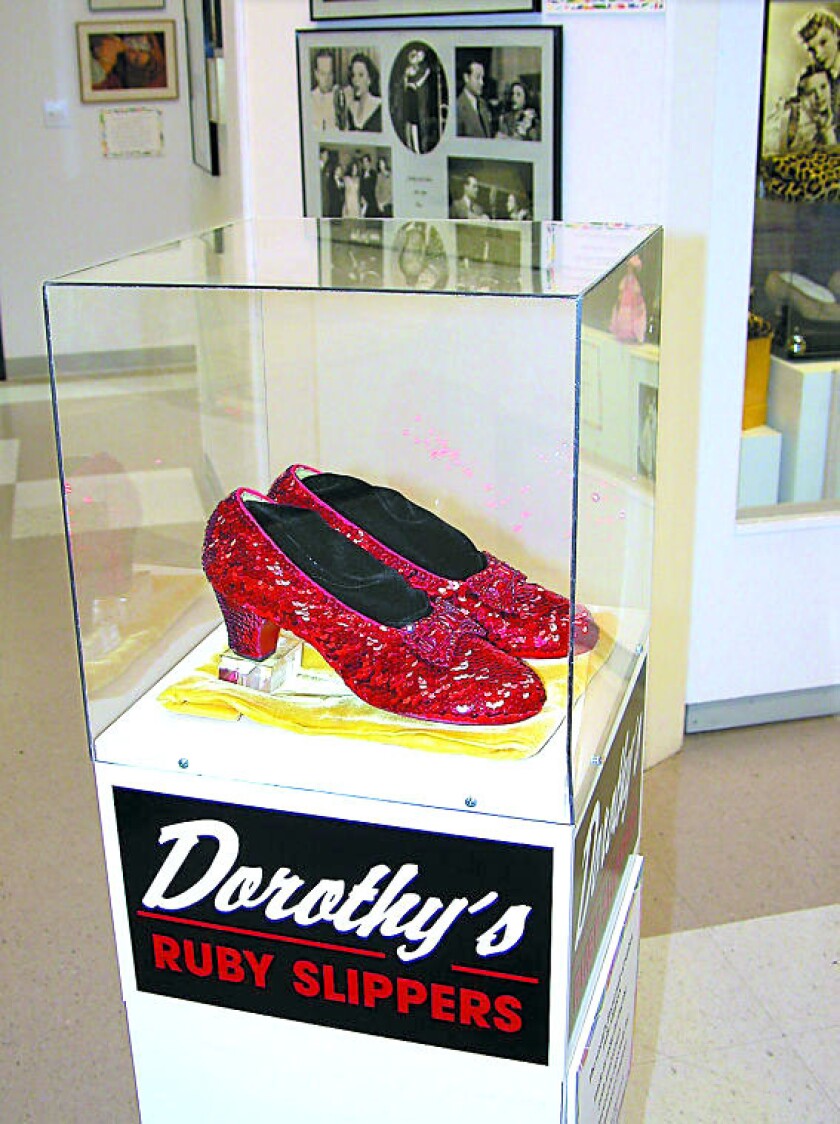

“That’s where they were stolen, right there. They were on that pedestal,” he said. “There was a Plexiglas top, just eight-inch Plexiglas, taped at the seams and screwed to the base.”

Not many people would want to revisit the worst moment of their life. Fewer would want to do it twice a week, with complete strangers.

Kelsh is obviously not most people.

FBI

Kelsh, the founder and executive director and curator of the Judy Garland Museum in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, now leads regular tours of what was arguably the worst moment in the museum’s history: November 28, 2005.

This morning, museum officials discovered the theft of their prized exhibit, a pair of Garland’s iconic “ruby slippers” from the classic 1939 film The Wizard of Oz.

The slippers were discovered by the FBI in a raid in 2018. This January, Terry John Martin, a rural Grand Rapids man with a long criminal record, pleaded guilty to the theft — the “end result” he wanted, his attorney wrote in court documents. Martin’s alleged accomplice, Jerry Hal Saliterman, of Crystal, Minnesota, faces trial in federal court on related charges in January 2025.

Tom Olsen / Duluth News Tribune

The Judy Garland Museum now offers visitors twice-weekly tours of the Ruby Slipper Heist.

Kelsch leads the tours personally, taking visitors through the museum and showing them where and how the slippers were stolen, what the crime scene was like when Kelsch arrived at the museum the morning of the theft, and what happened after the shoes were stolen.

The Theft Tour is available for advance registration each week on Friday and Saturday, $8 with purchase of a general museum admission ticket.

The tour is an inside and very personal look at a heist that sent shock waves through the museum, film history and art communities, but was devastating to Kelsch and the museum.

Jeremy Fugleberg / Forum News

Donations dried up, visitor numbers dwindled, and Kelsch and museum officials were inundated with rumors and accusations that the theft was an inside job.

The insurance company that now owns the slippers is putting them up for auction in December, where they are expected to fetch several million dollars. The museum plans to bid on them with the help of funds from the state of Minnesota, although the price could skyrocket.

Their heist only burns the couple’s worth.

The museum began offering the tours in May, and they have been a popular addition, said Janie Heitz, who became the museum’s executive director in 2021.

Visitors, many of whom had heard about the robbery, asked about it and the slippers. For better or worse, the theft is now also part of the museum’s history.

“People want to know about the history, and this is part of the history of our museum that he built,” she said they decided. “We can lean on him a little bit and hug him.”

“What happened was a perfect storm, a comedy of errors on our part,” Kelsch said as he led tour visitors through the museum. “You can’t make up a story like that.”

The pedestal that held the shoes stands near the center of the museum’s largest exhibition hall. Except now some of the items around it are for the steal itself.

Jeremy Fugleberg / Forum News

The ruby slippers stolen from the museum are one of only four known pairs in the world. Known as the “traveling shoes,” they were owned by Hollywood memorabilia collector Michael Shaw, who allowed the museum to display them in the summer of 2005 without a written agreement, Kelsch said. The museum agreed to pay the $1 million premium on the insurance policy.

Another pair of ruby slippers known as “the shoes of the people” are preserved at the Smithsonian Museum of American History in Washington, DC, probably surrounded by extensive security. Museum security around the Traveling Shoes was not so good.

The museum couldn’t afford a guard, but it did have a security system, Kelsch says. Also—there were significant gaps in motion detector coverage, and the only security camera pointed at the pedestal was not set to record.

“We thought about security, but we’re a small town and we have trust — there were a lot of lapses in our security,” Kelsh said.

Kelsch directs visitors to the side door, where officials found broken glass before spotting the overturned column that held the slippers.

“We’re going to look at the crime scene here,” he said.

Jeremy Fugleberg / Forum News

The building was new in 2005 and had no sprinklers, and kids kept running through the emergency exits, setting off alarms. The doors were disabled and Kelsch said he thought setting the night alarm also reactivated the doors, including that side door (it didn’t). The view of the entrance was obscured by the road ahead and the door was often left open.

This is the door that court documents say Terry John Martin smashed in with a hammer. No alarm went off. Martin took the shoes, knocked over the pedestal and dropped a single red sequin on the floor, a spot now marked on the museum floor.

The sequins were later used to authenticate the discovered slippers.

Jeremy Fugleberg / Forum News

Kelsch talks visitors through the aftermath, the loss of trust and credibility, the malpractice lawsuits, the drop in donations, the accusations, the rumors, the $1 million reward, the moments of false hope, the battle over the insurance claim, the economic aftermath of the Great Recession.

The years of fighting have clearly taken their toll on Kelsch, a pain that shows in his narrative in this back hallway. After a while, “we just wanted to forget about it,” he said.

A visitor to the tour, Julie Thompson of St. Michael, Minnesota, chimed in with some encouraging words. Thompson’s claim: There’s a lot more to the shoe story than the heist.

“It’s easy to dwell on this piece, but I hope the community and the museum, and you, with all your experience, will understand that this is just a small piece,” she said.

Kelsch agrees and seems determined to continue telling the story of the shoes.

“We didn’t want to talk about it, but now we can,” he said. “But after all these years, now that they’ve been discovered, we can feel better.

“They were not destroyed.”

The ruby slippers stolen from Judy Garland’s museum will be auctioned at Heritage Auctions in December – expected to be a high-profile event.

Photo provided by FBI Minneapolis

The museum intends to bid on the ruby slippers, hoping to recoup the display prize, said Heitz, the museum’s executive director. But she was tight-lipped about the status of their fundraising.

“John and I are optimistic, I’ll just say that,” she said.

For his part, Kelsch says he’s hopeful: “We’ll be there with our pockets full.”

Earlier this year, Minnesota lawmakers approved spending $100,000 to fill those pockets.

“We’re buying Judy Garland’s goddamn slippers to make sure they stay safe at home in Grand Rapids — on display for all to enjoy — under Ocean’s 24/7 11-proof security.” wrote Gov. Tim Walz on social media.

✅And we’re buying Judy Garland’s goddamn slippers to make sure they stay safe at home in Grand Rapids – on display for all to enjoy – under the 24/7, 11-proof security of Ocean.

— Governor Tim Walz (@GovTimWalz) May 30, 2024

At the museum’s side door, the one that was broken in the night of the theft, Kelsch mentions Waltz’s message and says that the museum’s security is now much tighter.

He tells how the slippers, if returned to the museum, will be displayed in an exhibit behind armored glass, buried in a safe.

“If we get them, we’ll have Fort Knox this time,” he said.