For the past 30 years, the state of Texas has voted Republican. Over the past five years, conservative lawmakers have passed a slew of laws aimed at a central, threatening idea — a liberal one college campuses. In the spring, the implementation of Senate Bill 17 at Texas public universities shut down all diversity, equity and inclusion programs, offices and training. The effects reached far and wide across the UT campus with the closing of many offices such as the Center for Multicultural Engagement and the Center for Gender and Sexuality, and later the disbanding of the Division of Campus and Community Engagement. In April, the university laid off about 60 employees who previously worked in DEI-related positions to better align with SB 17.

Legislative actions like SB 17 follow growing distrust of higher education and concerns about left-wing agendas on campuses.

In general, universities are considered liberal epicenters, regardless of the area around them. UT in particular is a liberal outlier in a conservative state.

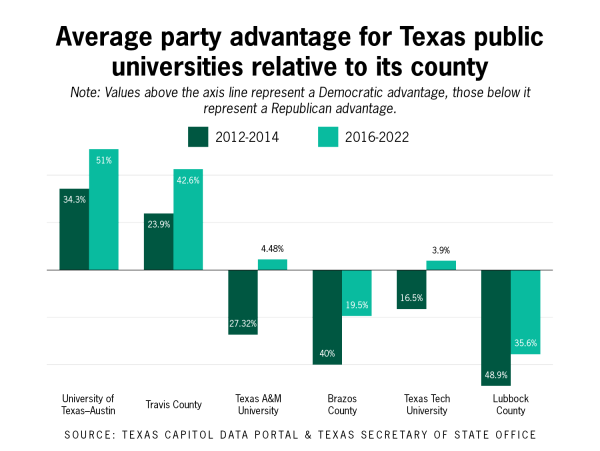

To explore this idea, The Texan gathered data to analyze election results over the last 10 years at three Texas public universities — The University of Texas at Austin, Texas A&M University and Texas Tech University. The data revealed an overall positive trend in the Democratic vote among college students at rates faster than both county and statewide. These changes are far from consistent across schools, but overall they demonstrate a noticeable leftward shift in the political attitudes of the state’s youngest voters over the past decade.

This shift correlates with the rise to prominence of Donald Trump in American politics in 2016. To reflect this shift, The Texan broke that data down by median party preference before and after the 2016 general election.

Travis County, which has historically voted Democratic, had a median Democratic advantage, or Democratic vote share minus Republican vote share, of 23.9 points before the 2016 general election. and 42.6 points after that. UT’s campus district had an average Democratic advantage of 34.3 points before 2016. and 51 points after that.

“When you look at UT, it’s probably not too dramatically different from a county that’s overwhelmingly Democratic to begin with,” said Josh Blank, research director of the Texas Politics Project. “To the extent that it is, I think you can probably just chalk it up to age.”

According to the Pew Research Center, about 66% of voters aged 18 to 24 identify with the Democratic Party in 2024.

Texas A&M and Texas Tech University, generally perceived as more conservative campuses, present a different story.

Located in South Central Texas, Texas A&M’s Brazos County had an average Republican advantage of 40 points before 2016, which was cut in half to 19.5 points in 2016 and beyond.

In a significant shift, Texas A&M had an average Republican advantage of 27.3 points before 2016, but flipped to an average Democratic advantage of 4.5 points in later elections. On average, the university voted 9.2 points more Democratic than Brazos County.

Texas Tech’s Lubbock County, located in Northwest Texas, averaged a significant Republican advantage of 48.9 points before 2016, which decreased to 35.6 points in 2016. and after that.

However, campus districts averaged only a 16.5-point Republican advantage before 2016, with a reversal to a 3.9-point Democratic advantage in later elections. On average, the university voted 17.9 points more for Democrats than Lubbock County.

Texas A&M saw the largest increase in its share of the Democratic vote, while Texas Tech differed most significantly from the vote of its encompassing district.

However, these trends are probably not an indicator of disproportionate liberalism on college campuses. Rather, they are a reflection of the changing political environment in the country, Blank said.

“Are all campuses liberal?” Blank said. “No, but they are responding to politics. What you see here is that even formerly Republican campuses in the Trump era have moved into the Democratic column in some pretty remarkable ways.

More broadly, the change can be explained by the way political ideology has become increasingly intertwined with partisanship over time, said

Talia Stroud, professor in the Moody College of Communication’s Department of Communication Studies and founder of the Center for Media Engagement.

“It used to be that you would have conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans,” Stroud said. “And while that still exists to a small degree, it’s much more likely to find people who are consistent in their ideology and partisanship.”

Psychology and humanities sophomore Cara Burks, a member of the University Democrats, said she was drawn to UT in part because of its reputation as a liberal school in a conservative state. Although Burks grew up in a conservative household, she said her daily experiences as a woman with type 1 diabetes and her advocacy work in disability communities have shaped her political perspective.

At the state level, Burks said she believes the political climate in Texas over the past few years, including how politicians deal with gun violence, women reproductive health and homelessness motivated students to vote more Democratic.

“I think it’s just great past experiences that people, especially on the UT campus, have had,” Burks said. “Seeing how we were left behind was that wake-up call (that) something had to change.”

Some students prefer to engage in politics in a nonpartisan way, like civil engineering junior Vincent Tomasetti. As vice president of TX Votes, a civic engagement organization on campus, Tomasetti serves as deputy registrar of voters during election seasons. He finds satisfaction in ensuring that prospective voters are informed about their ballots through drop-in events and nonpartisan voter guides.

“A lot of students have political beliefs that they don’t necessarily know how to represent,” Tomasetti said. “We all have our own personal beliefs, what we see in the world, and that affects how we’re going to vote.”

Members of the Young Conservatives of Texas, the College Republicans of Texas and the UT chapter of Turning Point USA did not respond to requests for comment. However, in an article from The Hechinger Report, conservative students from across the country at the Republican National Convention in July expressed concern about free speech on college campuses, left-leaning faculty and staff, and the lack of ability to engage in productive discourse with peers of different political persuasions. Many said the college experience and exposure to liberal faculty and students only hardened their Republican beliefs.

Regardless of ever-changing university policies, students represent the changing nature of American politics, the shifting priorities of the electorate’s youngest voters, and the diversity of political leanings at community colleges across the state.

“There is no one story,” Blank said. “What you’re really seeing is the politics of the last decade reflected in the attitudes of young people.”

Note: This data was compiled using Vote Count District (VTD) results of areas covering college campuses and surrounding areas where most students tend to vote. It includes only the offices of president, governor, and U.S. senator for general and midterm election years from 2012 to 2022. Because these districts include the votes of everyone who votes within their boundaries, the results may include some non-student voters, such as faculty or community members, and do not account for students who vote elsewhere.