On Halloween morning, the tenants of 63 Tiffany Place gathered outside their Carroll Gardens apartment building to ask for the nearly impossible.

They wanted their landlord, Irving Langer, to sell them his building.

“Trick or treat, don’t cheat, you have to meet the tenants,” chanted tenants, activists and elected officials, including NYC Comptroller and Choir Director Brad Lander.

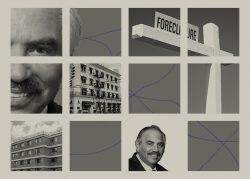

Langer was not in attendance — despite the cardboard cutout of the one-time 10th “worst landlord” — and did not respond to a request for comment.

His absence was pointless. The demands of the tenants were largely indicative.

They had tried to get Langer to sell before the buildings’ low-income housing tax credit, which had kept housing affordable for 30 years, expired in 2025. A nonprofit agreed to buy the building and keep its affordable housing units, they said, but Langer had broken off communication, leaving them without leverage.

All of this would be different if the Tenant Affordability Act had passed.

“This is what should stop TOPA and get us to focus on preserving what’s left of affordable housing in New York City,” Assemblywoman Marcella Mittain, who sponsored the act, said of the plans for Tiffany Place, which she argued , that will create rents and pushes out tenants.

The bill, which has been floating around Albany since 2020, gives tenants the first chance to buy their building if the landlord wants to sell it.

That will put a sale on hold for a few months so tenants can talk to the city about a grant, the bank about a loan and put together an offer, explained Cea Weaver of Housing Justice For All. Tenants can come together to form a cooperative and collectively manage the building.

But more often, tenants use TOPA as a “bargaining chip,” Weaver said, citing cases in San Francisco and Washington, D.C., that have passed versions of the bill.

For example, if tenants know their landlord wants to sell, they can offer to waive their right of first refusal in exchange for a five-year lease.

Or they could cede their TOPA rights to a nonprofit that could buy the building — a strategy that would most benefit Tiffany Place’s tenants. With a non-profit organization, the building could remain available for rent.

Weaver said TOPA has support in Albany — “people love it” — but it’s unlikely anything will pass before TIffany Place’s LIHTC expires. That means Langer can sell, as activists say he wants to do, and the new owner can raise rents to market levels.

What’s still hazy is whether Good Cause Eviction, other bill activists tied to the 63 Tiffany Place fight, will protect tenants from rent hikes when 2025 rolls around, activists said.

About half of the units at 63 Tiffany are rent stabilized, meaning they won’t face a rent increase when the LIHTC expires, explained Maria Vaelo-Calderon of TakeRoot Justice, which represents 63 Tiffany Place.

For the remainder, Good Cause must effectively limit rent increases to 10 percent or inflation plus 5 percent, whichever is lower. If the increase exceeds this threshold, the tenant will have eviction protection in housing court.

Good Cause does not cover state-regulated units that are rent- or income-restricted, Vaelo-Calderon said, meaning the unregulated units at Tiffany Place will not receive the protection while LIHTC, a federal subsidy, is in effect.

After the LIHTC expires in March, the attorney said those tenants will likely be covered by Good Cause. But the owner can argue in court that the large rent increase is justified given the loss of the subsidy.

Read more

Tenants are looking for an opportunity to buy. Landlords: Go ahead

Multifamily giant Irving Langer pays off delinquent loan after selling properties

Real estate professionals call the tenant absorption bill wrong