Artists often use their surroundings to influence their work. In the case of Birmingham artist Joe Minter, his sculptures cannot be separated from his life in the city – literally.

A site-specific exhibit in Titusville recently honored Minter’s legacy. “Joe Minter Is Here” highlights Minter’s life and work. The exhibit, housed in a century-old steel foundry called Marc Steel, is designed in a circular, labyrinthine style. It worked as a history museum and as an art museum. Visitors saw Minter’s work, but also learned more about him.

Tyler Jones is the exhibition’s creative director. He said the location has a connection to Minter’s history.

“He applied for a job here in the late 1980s and early 1990s during a period of unemployment. He and his brother were taken by the Bull Connor police and wrongfully arrested. His brother was assaulted by the police across the street in what is now Memorial Park,” Jones said.

But Minter’s work was also an aesthetic match for the warehouse.

“The nature of his work, made of steel, iron and industrial texture, really feels this place that made train wheels over a century ago.”

(Bob Miller/1504)

Minter creates sculptures using discarded objects. Car wheels, bicycle gears, chains and scrap metal are staples of his works.

“Particularly in his work, using discarded materials, found objects, to make these connections between what he would say were discarded people,” Jones said.

He felt it was important to recognize the foot soldiers of the Civil Rights Movement. His work aims to speak for those who tend to be forgotten.

Although there is social and political commentary in Minter’s work, there is also an element of fantasy and joy.

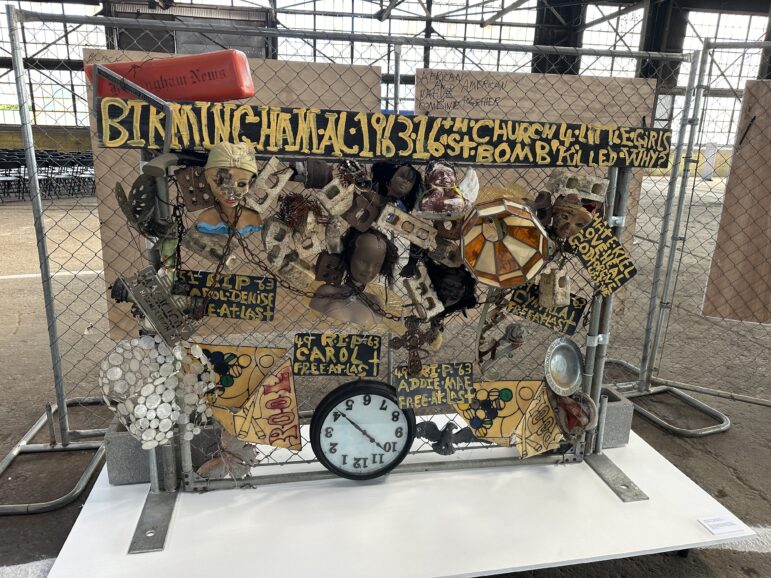

(Kelsey Shelton/WBHM)

In his coverage of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, the found objects add to the whimsy. The four girls who died in the attack are depicted with rag dolls. The glass pieces are made to look like stained glass. Doves and butterflies are woven into the parts of the fence.

Minter’s art shows a different America—one in which atrocities are foregrounded and the flag symbolizes oppression, not freedom. But it is also an art that describes survival. Which finds joy in pain.

Minter Open Air Museum

(Carrie Norton/1504)

Minter became part of a Deep South tradition called yard shows. Many black artists resorted to yard exhibitions because art museums were segregated.

“Although you may not have access to the museum, the courtyard became a place to express your ideas about the freedom movement,” Jones said.

Minter’s most popular sculpture collection, The African Village in America, is on display in his yard in Titusville. The street he lives on is littered with his works. This is an introduction to what you can expect to see in an African village.

On that day, Minter came to the front door wearing goggles and a helmet covered in “I Voted” stickers. He showed off the space he considers his studio, a concrete patch near his front door. Minter said that when it comes to the studio, he’s happy to use nature.

“God connects with you by what is around you. All that, all the stars and the moon and the universe, and God is looking down and can see everything you do,” Minter said.

The space was surrounded by African-inspired sculptures and signs written in his signature script. One piece was recently repurposed from a sign she found at a Goodwill store. Minter said everything in his art is about Birmingham.

“And when I say everything, the brutality and the humiliation of being yelled at and beaten and taken off the street and thrown into the steel mill,” he said.

(Kelsey Shelton/WBHM)

The African Village is located in the backyard. Minter called it an ancestral graveyard. He said his artistic medium in his home documents 400 years of the black experience.

The sculpture field was a breathtaking sight. It represents one man’s work to allow enslaved blacks to rest in peace. To end this tour, Minter took out his drum and beat a beat for those who lost their lives during the slave trade.

(Kelsey Shelton/WBHM)